The Sangha We Have

(Follow this link to see the October 2020 Priory Newsletter where this was originally published.)

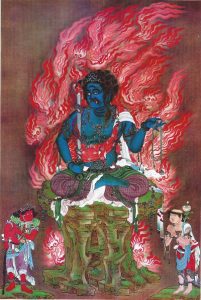

Fudo, who’s full name – Fudo-Myo-O – means “The Immovable Bright King,” reminds us that we can sit still amidst the flames of greed, hatred and delusion!

My teacher used to say that Buddhism is for human beings; it is a religion, or spiritual practice, for regular people. Sometimes though, I have noticed myself hoping for a community of practitioners who are somehow perfected or at least more perfected than I am; I find myself hoping for something other than a sangha of human beings. A simple general definition of sangha is a community of people dedicated to helping themselves, and us, to awaken to the deep Truth of life.

I suppose that I, and perhaps others who think along these lines, think that if I associate with people who are perfect in their practice, it will somehow be easier for me; like if the people I associate with are always kind and gentle and smiling, then I won’t have to get angry: problem solved, right? But the thing is, as I associate more with long term deeply accomplished practitioners, I have begun to more deeply recognize that they know that no matter how perfect they are, they can’t actually do my training for me: they can’t do the work of uncovering why I might get angry, or whatever, and bringing that reason to peace. The solution of having other people be perfect is just a temporary fix (what happens when get back out among all the other imperfect people?) while what the Buddha offers to us is profoundly deep and long lasting. What the Buddha offers us is not dependent on whether other people are perfect or not. So, maybe hoping for a perfect sangha is not really all that helpful?

One thing we may not recognize is that we help to create the sangha that we are in. It is true that we help create the sangha that we are in, no matter how we think of sangha: of course, there is the sangha of our immediate community of people doing their level best to put the Buddha’s teaching into practice. But sangha could also mean our immediate family; our circle of personal friends; our coworkers; the people in our neighborhood, city, state, country, world. I have come to view all these human beings as the community of beings helping me to awaken to the deep truth of life, even though they may not realize that that is what they are doing. We may have a sort of diminishing influence as the sangha we are thinking of increases in size or distance, but we do have an influence. We can’t really not have an influence either for good or for ill.

There are a few things we can always do to help with how we harmonize with our sangha, to help influence it for toward the good. It is understood that keeping the precepts, with meditation, is the foundation of practice and if we do not work toward keeping the precepts, in detail, on a personal level, everything else begins to fall apart. Beyond our commitment to keep the precepts, there are many important things that help with the harmony of the sangha. Today, two in particular stand out.

Related to the precepts is the quality of taking responsibility for our own suffering. This is a hard one, and volumes could be said about it. But hard or not, taking responsibility is critical in our own liberation. The more I can pause, look at my own mind, impulses and actions with as much honesty as I can muster and admit where I am or might be creating suffering, the more things tend toward harmony. After admitting to the possibility of the distortion or attachment that creates suffering, there is then the work of being willing to do something about that.

There are many ways that we might not take responsibility for our lives and put the cause of our own suffering on to someone or something else. One sign that I am not taking responsibility is when I indulge my complaining mind or my paranoid mind, but there are others and a way we can go with this, is to just remind ourselves that if we are affected by something within ourselves or outside of ourselves we can train ourselves to respond from a place of training.

There is a variation on not taking responsibility where someone or some circumstance points out a fault – a behavior or attitude that creates suffering – in us; when we hear the pointing we argue that, because the words used don’t exactly match up with our experience, or they were said tinged with some form of emotion or upset, whatever is said is invalid. This is clever but sad, since it just further prolongs our suffering.

Following taking responsibility, is the practice of sympathy. In the Shushogi, Dogen says: “If one can identify oneself with that which is not oneself, one can understand the true meaning of sympathy: take, for example, the fact that the Buddha appeared in the human world in the form of a human being.” When I think of this, I like to think that maybe the Buddha did not have to take rebirth as a human being who gets sick, old and will die, and has to put up with people throwing rocks at him and spitting on him and whatnot. Perhaps he could have just decided to stay in the heaven realm where he was, and enjoy himself? That the Buddha appeared in this world and stayed here to teach the Dharma is an unlooked for (and, I actually think, undeserved by me) grace for us human beings. It is the compassion of the Buddha that made him willing to be with other human beings and endure the hardships that are inevitable when spending time with the people of our world.

Sympathy is one of the four signs of enlightenment and on the most basic level, if there is not some sense of sympathy for the plight of others working in us, we are far from the awakened mind of the Buddha. I deliberately include sympathy after taking responsibility, because there can be a tendency for us to think something like: “through hard work and taking a small (if we are in this state of mind, we probably wouldn’t say small, but that is what it amounts to) small amount of responsibility for my actions, I have created some good fortune for myself; the suffering of those around me is the result of their own actions and has nothing to do with me, so why don’t they belt up and get to work? It was hard for me, but I’ve got mine, and they are on their own.”

There are some teachings in Buddhism that say that, if we found ourselves in a situation where help was not forthcoming in our hour of need, it was due to our hard-hearted unsympathetic actions from the past; this is one of those un-provable parts of the Dharma and I am neither advocating adopting this view, nor not adopting it, but it may be useful to reflect on. Having seen some of the idiotic and mean spirited ways that I have behaved in the past and the consequences resulting from that behavior, I think it is a bit of a miracle that I even heard about the Dharma and I certainly can’t take it for granted that I am entitled to it or any small good fortune. Certainly, for me, because of seeing this suffering created by myself, if I see someone in need, I am going to at least listen very carefully to them and see if there is something I can do to help.

Anyway, sympathy is helpful in creating harmony and helps us to create wise ways of helping beings. We lose nothing by giving the help that we feel we did not receive, to someone else in a similar situation to ours. Let me repeat that: we lose nothing by giving the help that we feel we did not receive, to someone else in a similar situation to ours.

There is a story that I like from the life of the great Japanese zen master Bankei Yōtaku (1622-1693). Bankei would hold retreats for a great many people, inviting whoever would like to attend. At one retreat there was a person who had the habit of stealing other people’s possessions and Bankei’s students brought the matter to Bankei. They asked Bankei to have the person leave. Bankei is reported to have said that no, if someone were to leave it should be the reporters, since they already had virtue and could tell right from wrong. The thief, on the other hand, was precisely the person who should stay, since they needed the most help. Happily for everyone involved, when the thief heard about Bankei’s kindness, he was moved to mend his ways.

It has turned out that for me, I have discovered that the sangha that I have right now, the sangha of the regular human beings around me is the perfect sangha for me. (And I am really grateful that you all put up with me!) It is perfect in that it has helped me to see more clearly, when I look through the lens of my practice, how I influence the world by creating suffering and also how, again with the aid of the Dharma, I can stop creating suffering, and bring a little bit of compassion, love and wisdom into the world.

We usually cannot take away someone else’s suffering, but we can do a lot to help each other and even just a sympathetic listen to someone who is suffering can be a help in creating harmony in our sangha.